Information and updates on Virga Records releases.

Virga Records has been established to release new and archival material from contemporary composers working in a wide variety of styles and media. While the label will represent contemporary classical, ambient, radiophonic sound design, niche beats and found sounds, other older and newer styles will be also be welcomed.

Our name is from a word that has two meanings: rain that evaporates before it reaches the ground, and a style of notation from ancient music manuscripts. The name represents two important principles – a deep respect for the origins and histories of music traditions, and a recognition that atmosphere is one of the most important elements in music.

Some releases on Virga Records will be online only, and some will have mixed online/physical releases. Some may be physical only.

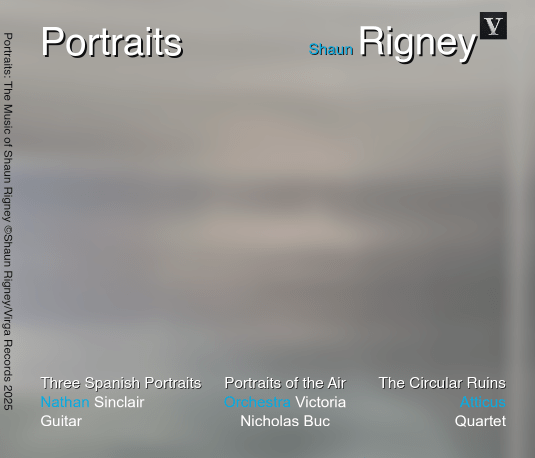

Portraits – Virga 001 – CD and Digital Release Notes

For purchase enquiries, contact the composer directly shaunrigney@yahoo.com

Each CD comes with a hi res (96k 24 bit) download code.

What makes a composer want to write a symphony in the 21st century? It seems like a strange choice of musical form for an epoch that may well be remembered mainly for the rise of social media and sea levels. How can a symphony hope to speak to such a time?

The symphony has proven to be an adaptable form in the same way that the play has endured as a theatrical form. Beckett and Shakespeare were both writers concerned with the human condition, and each chose to use the play to express complex and nuanced ideas. It seems that the play was often the most suitable form for these two writers separated by time and temperament. Likewise, the symphony has proven flexible enough to house ideas, from many different schools of thought, across three centuries.

The symphony, like the play, is more cart than castle, that is, transportable, adaptable and scalable. It has, at various times, been hidebound by rules and dogmas, but it endures because no one has the authority or the right to say what a work must or must not contain to qualify as symphony. From the smaller models of Haydn and Mozart, to the triumphalism of Beethoven, to the gigantism of Mahler, the symphony has evolved in parallel with the musical thoughts that it sustains. Why, then, does it survive?

The symphony is a vehicle, not a style. Composers have turned to it to express all kinds of ideas, lightness, heaviness, awe, quietude, to develop themes, and to express very big emotions. Beethoven and Shostakovich occasionally share a common desire, across the centuries, to express their feelings about great social upheavals in symphonic form. Sometimes, the form itself morphs beyond its already imaginary boundaries towards new shapes, and even other art forms. Schönberg composed a symphonic poem, Pelléas und Melisande, and Debussy gave us La Mer, trois esquisses symphoniques pour orchestre (Three Symphonic Sketches for Orchestra). Considering the exquisite detail of the finished work, it is reasonable to suppose that Debussy considered La Mer to be a fully realised work. The finished movements were not sketches understood as preliminary plans, but sketches as understood in the visual arts.

My second symphony, Portraits of the Air, also references the visual arts. It was composed as a response to hundreds of photographs of the sky, sent to me by volunteers in a collaborative art project.

I have been fascinated by the sky since I was a child. Very early in my composing career, I had planned a series of improvisations inspired by the clouds of John Constable (1776 to 1837), the English landscape artist who understood the sky so well. While the opportunity to create that work has yet to materialise, I did create a work called A Portrait of the Air for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2004. My second symphony recalls that earlier title and subject matter, but the similarities end there; the previous work used text and electronic musical means to create a succession of musical tableaux. The symphony, Portraits of the Air, follows a different path.

Like Claude Debussy, I have been profoundly influenced by the art of painting. I am fascinated by the technique of sfumato, perfected by Leonardo da Vinci, where gradual transitions occur from one colour to another, one texture to another, or one region to another. It is, essentially, a blending technique. I have adapted this technique to orchestral colours. In traditional orchestration, colours, or timbres, are usually achieved by combining instruments in blocks of sound. In Portraits of the Air, instruments are often combined using gradual transitions called crossfades, so that timbres are not fixed – they are dynamic, changing. This technique, when applied to large groups of instruments, I call orchestral sfumato. When used with one or two instruments, the effect is somewhat different, creating a change of lighting that I call orchestral chiaroscuro.

Portraits of the Air is not in sonata form; rather, it consists of 11 themes, which occur throughout the work, in different guises and different styles of instrumentation. The French symbolist poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, once called the rose of the poet the “flower absent from every bouquet.” The 11 themes of the symphony could be said to represent the 10 cloud types plus an 11th – the cloud absent from every sky.

An edit of this recording of Portraits of the Air was used in the installation Sky Symphony, based on my research Creating A Collaborative Symphony.

The Three Spanish Portraits for guitar solo were commissioned by Australian guitarist Paul Nash, a lifelong supporter of the guitar and its music. Paul is a devotee of Andres Segovia, the Spanish classical guitarist who almost single-handedly resurrected the guitar as an important solo instrument in the middle of the 20th century, after it had languished in the wilderness following its immense popularity as a salon instrument in the 18th and 19th centuries. In acknowledging his love of Segovia’s playing, Paul commissioned works from me in a style that Segovia himself might have looked on favourably.

Segovia was notoriously forceful in his musical opinions, to the extent of shunning works that he himself had commissioned. Who can say what Segovia might have thought of these works; nonetheless I chose to represent three great figures of Spanish music, Albéniz, Granados, and De Falla, each one a composer whom Segovia had honoured with his musical attention. My portraits pay respect to some of the characteristic turns of phrase of each composer, without resorting to imitation.

The string quartet The Circular Ruins takes its name from a story in the collection entitled Labyrinths by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899 – 1986). Although not a portrait in the sense of the other works on this release, there is a strong presence of Borges in this work, a kind of musical outline or shadow.

In The Circular Ruins, Borges, ever fascinated by themes of eternity, the labyrinth, circularity, reality and illusion, writes that “modelling the incoherent and vertiginous matter of which dreams are composed was the most difficult task that a man could undertake,” and although the protagonist in this story is actually attempting to dream another being into existence, Borges might well have been writing about any act of creation – composition, for example, or the performance of a musical work.

My use of the title also refers to circularity as a concept in western classical music. The structure of the harmonic series (the acoustic division of a vibrating string or length of pipe into tones called fundamentals and partials) is implicated in the structure of western key signatures. Musicians often refer to the ‘cycle of fifths’ to explain how the movement from one key to another is established in so-called tonal music. One may start at the simplest key (C major) and arrive back where one began after travelling in a circle of fifths through all of the sharp key signatures (in one direction – arbitrarily, let’s say clockwise) or all of the flat key signatures (in the other direction, say anticlockwise).

For mathematical reasons concerning the ratios of the tones in the harmonic series, there is actually a small difference between the terminus and the starting tone once one has passed through this cosmic circle; the “beginning” and the “end” do not exactly coincide in nature. This difference is called the Comma of Pythagoras, and I have often wondered what Borges would have made of this tantalising fissure in the Platonic world. The cycle of fifths was especially important during the so called ‘Classical’ era of western music. But since the beginning of the twentieth century (roughly speaking) this structural element has become gradually less crucial (another ‘circular ruin’). The mathematics of the harmonic series no longer provides the axioms on which composers are expected to base their systems – yet the harmonic series remains a sort of fixed truth on the ever-shifting sands of harmonic allegiances.

At the conclusion of the Borges story, set deep in the jungle amongst the circular ruins of a temple to a forgotten god, the man who has been attempting to dream a new being into existence discovers that it is he who has been forged in the dream of another.

***

I would like to thank all of the dedicated and supremely gifted musicians and their supporters who appear on Portraits:

The members and support staff of Orchestra Victoria, which also happens to be the orchestra that recorded my first guitar concerto over two decades before;

Nicholas Buc, the conductor with Orchestra Victoria who translated my symphonic ideas into musical action so fluently and with such élan;

Nathan Sinclair, the fiery and super talented guitarist who understands my musical aims so intuitively; and

the members of the Atticus Quartet, Zachary Johnston, Lizzy Welsh, Phoebe Green and Judith Hamann, whose account of The Circular Ruins is so brimming with energy and atmosphere.

I would also like to thank my co-producer at the ABC Alex Stinson, engineers Nicholas Mierisch and David Wilkinson, Simon Polinski for additional audio post, Michael Letho for his help, advice and encouragement, my daughters Miri and Elli, and of course Rudie Chapman. I would also like to thank Slava, Len and Reuben, who have shown faith in me, and whose friendship and collaboration have given me inspiration and hope.

Lastly, to my friend and great supporter Daniel Tokarev, whose many wonderful photographs grace my website, you know how important you are!

Virga Records Premiere Release

The Flat Moon (Virga 003) is the first release on Virga Records (001 and 002 were prepared for release prior to 003, but there is still some work to be done). The Flat Moon consists of a single track, called A quiet space, which is just over an hour in duration. There is also a 6 minute edited version called A quiet space (Door A) in the playlist.

https://www.youtube.com/@VirgaRecords

A quiet space is is a mixture of electronic sounds, occasional beats, the call of a local currawong, and classical guitar. The guitar is a beautiful handmade instrument by Northern Rivers local Andrew Doriean, called La Grande Bouche (The Big Mouth), an exquisite instrument that is fun to play 🙂 This instrument also features on a forthcoming release, No Train Today (Virga 002).